If you had told me…

How many times have you heard someone start a sentence like that? “If you had told me two years ago that I would be making a billion dollars per minute just for eating cheese with a wooden spoon, I would’ve laughed in your face!”

You’re right, Karen, two-years-ago-you definitely could not have predicted that outcome. Despite our desire to believe that someone can predict the future, lifestyle changes and career 180s are inevitable. We can’t always plan for the exact future we want, but we can at least mitigate the stigma around changing your mind.

Why is it often considered a bad thing to change your mind? Change your career? Change your plans? Change your life?

To put it simply, change is a form of uncertainty, and uncertainty breeds fear. When things are not constant, we find ourselves becoming wary and suspicious of its merit. As someone who has willingly changed their life in a myriad of ways, I am of the belief that change is an opportunity for growth and discovery.

Of course, I didn’t wake up with this mentality; I had to learn it. And, because I’m a human person, I still struggle with it.

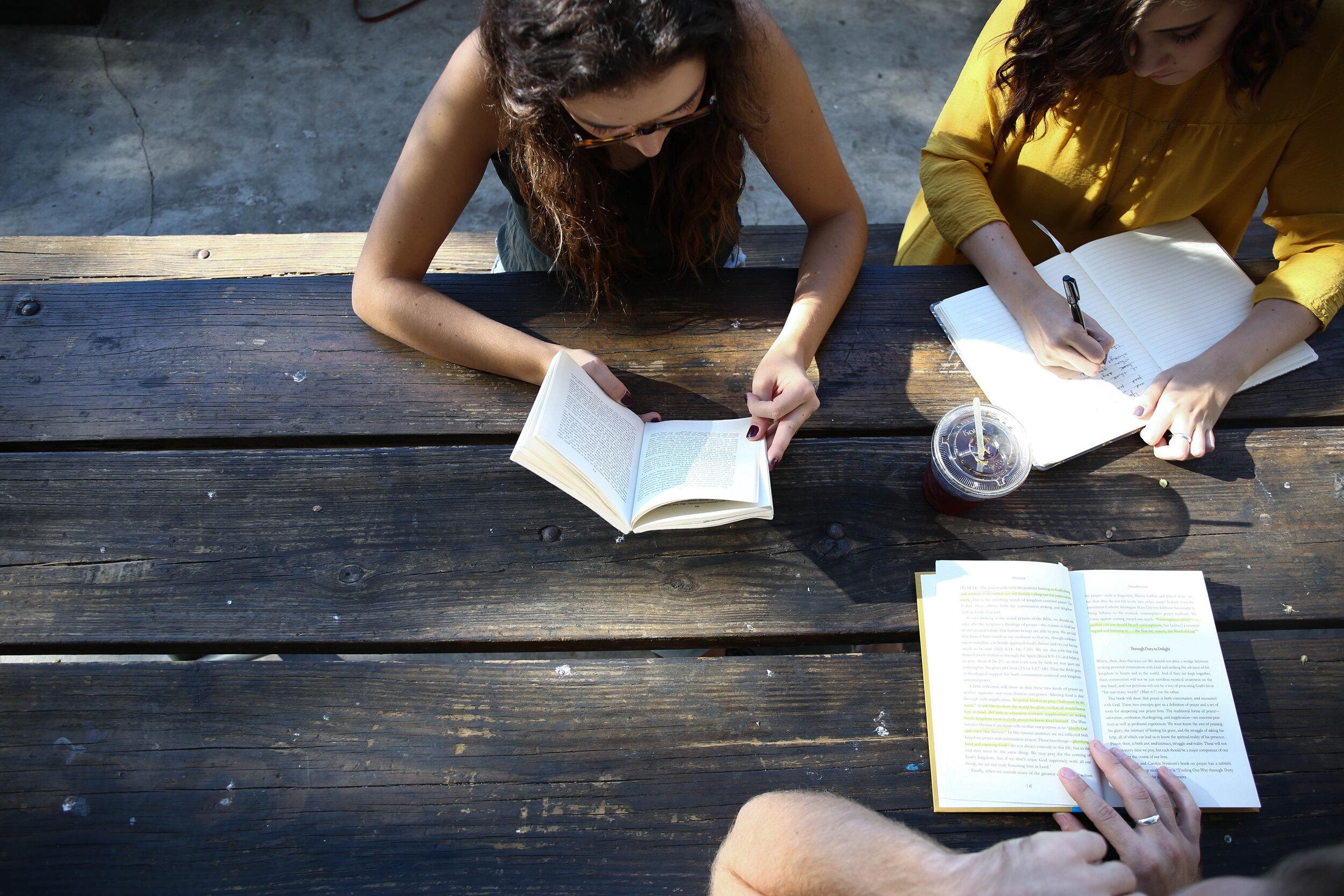

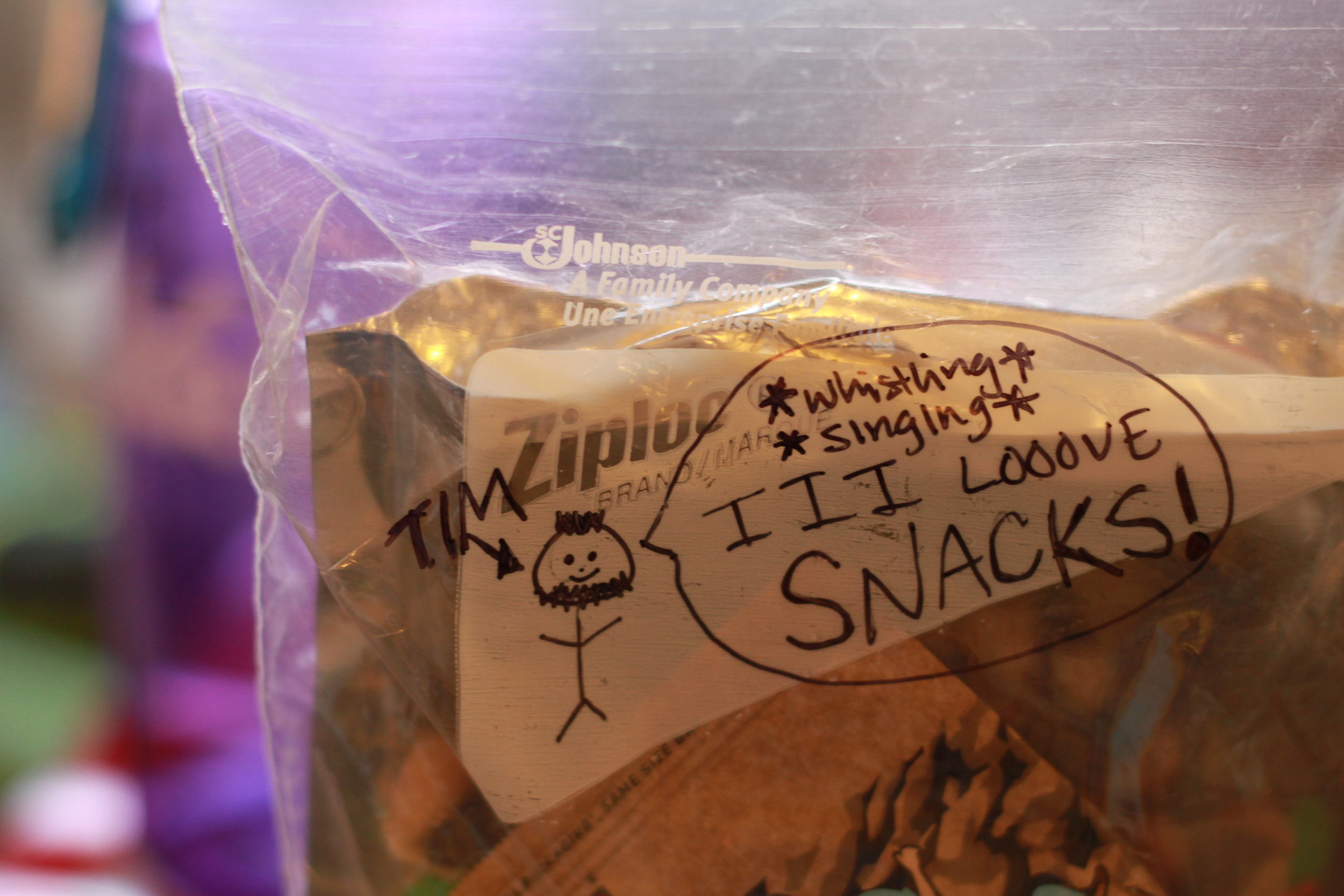

About two years ago, I set out on a month-long trek across Northern Spain with my mom. We were following the Francés route of El Camino de Santiago - an infamous pilgrimage from the border of France heading west to Santiago de Compostela, Spain. When you start the 500 mile trek along El Camino de Santiago, it is tradition to set an intention for the journey. Along the way, you ask/answer others about “the call to walk.” Everyone’s reasoning is different and a large part of the intrigue of this trek is being exposed to their unique purpose. I found this part of the journey the most satisfying - the instant camaraderie and unwavering support of everyone’s personal goals made walking in blisters much more tolerable. Also, wine.

My intention for the Camino - along with spending time with my soulmate mother - was to find meaning in something I’m very good at but often unsure of how to manage properly: listening.

I have the tendency to use my skills as a “good listener” to better myself and the situations I’m in. I listened to myself when I wanted to work for a magazine. I listened when I felt unappreciated as a young entry-level employee at a startup company. I listened when I felt burnt out, overworked, underpaid, and unhappy. I did all of this “listening” to make a change for the better, but I still felt empty. My listening skills were useful but seemingly unfulfilling.

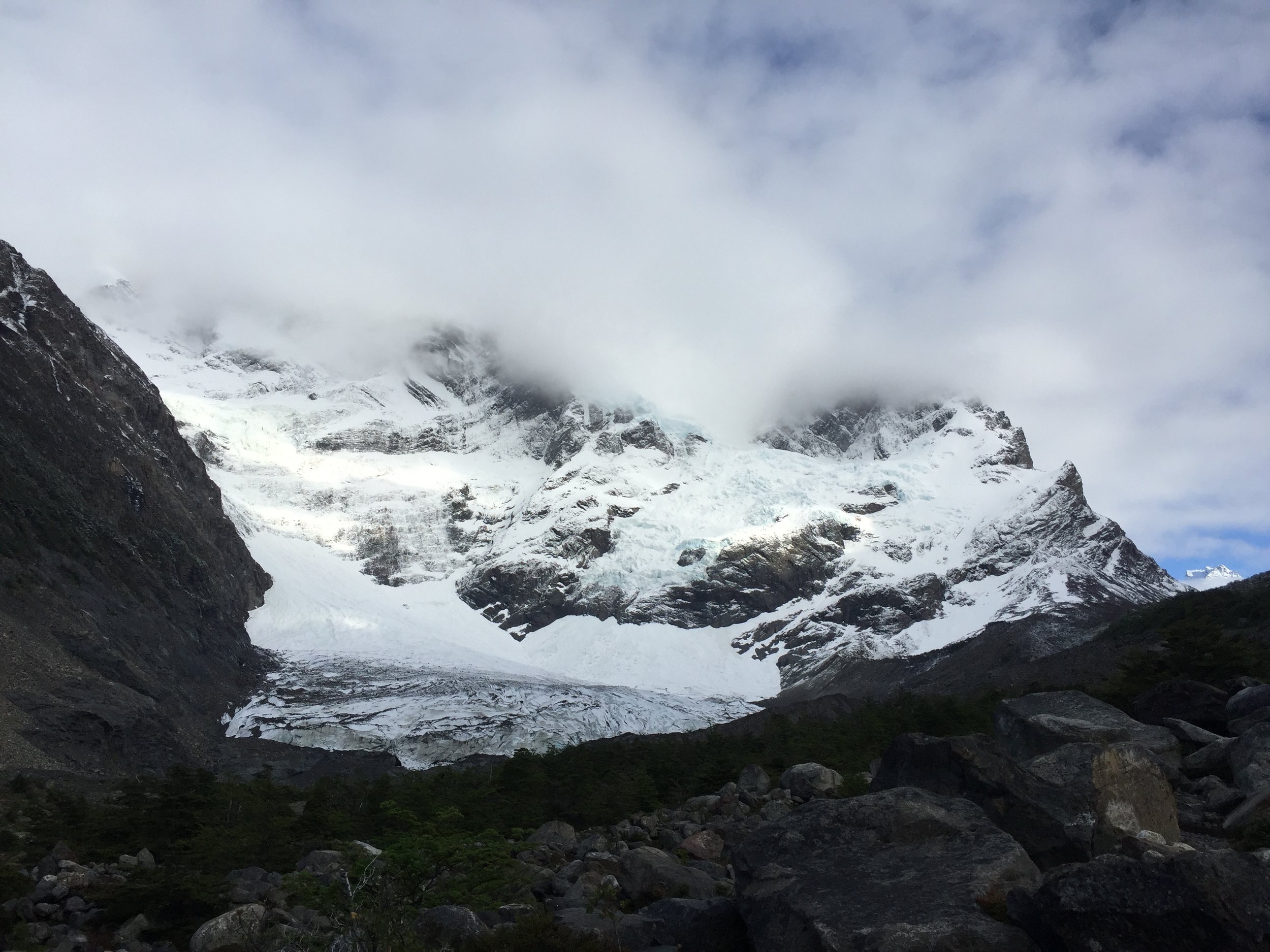

On the Camino, we found ourselves constantly walking through different types of weather and terrain, and every time something would change, we would adapt. We circumnavigated parts of the trail that were too muddy to trek; we put up and took down umbrellas; we rushed to escape wind at the peak of a mountain and slowed down on the steady inclines. The most daunting, however, was the fog. The thick, daunting fog engulfed us in the early mornings making it impossible to see even 5-10 feet ahead. We were blindly following a trail with no real idea of what was ahead of us.

Do you see where I’m going with this?!

The Camino forced us to listen - to ourselves, our surroundings, and to each other. We relied on our most basic senses to stay safe, motivated, and on track. Despite the fog clouding our vision of the impending destination, we found clarity in listening to our instincts.

I LOVE this metaphor because I have not always been a catalyst for change. I didn’t always treat “change” with the appreciation that I do today. This came as a life lesson after traveling for a living and being forced to adapt to unfamiliar scenarios. The ways in which I came to accept this detour-filled lifestyle are best represented in these four categories: understanding, acceptance, planning, and opportunity. Also, wine.

UNDERSTANDING

There is nothing worse than someone telling you to calm down in a stressful situation. I often refer to my time as a Marketing Coordinator at a law firm as The Wildfire Years. Things were constantly changing for no comprehensible reason. Lawyers like to change their mind…and those of us on the receiving end are forced to adapt quickly. This made for a very toxic work environment at times - because opinions and capabilities differ greatly across a department and not everything is as easy as a “can you do this yesterday?” email. Communication, as usual, is key. Gaining a solid understanding of the what, who, when, where, why, and how massively decreases the possibility of confusion, frustration, and the tendency to react instead of respond.

The understanding of possibility makes a huge difference as well. Sometimes things just can’t be done, but perhaps there is another way. A previous manager I had was amazing at seeing the possibilities - nothing was impossible, we just had to change course.

When a major shift presents itself, ask questions. Ask all the questions. Pepper the room with questions - I guarantee there’s a new hire sitting near to you just dying to hear the answer.

ACCEPTANCE

Change is inevitable. The sooner you accept it, the sooner you are able to control your reaction to it. In the many times I’ve had to switch to plan B after a flight has been cancelled or an apartment stay didn’t pan out properly, I found that accepting the situation as it was in that moment helped me calmly make other plans. Quitting my job and moving to Thailand was a giant “wtf” in every capacity, but I made the decision and the only way for me to thrive was to accept the change and get started.

Acceptance is a fickle thing due to our minds being able to rapid-fire panic in the form of “easy ways out.” You know how it is - your heart is beating fast, you feel hot and sweaty, and all of a sudden you realize you’re on WebMD and positive you’re having a heart attack. You’re probably not (fingers crossed?) but your brain has the ability to lead you straight into Panic City. I’m not lying when I say I’ve found myself sitting on a metal folding chair at 3am in the Riyadh airport audibly coaching myself into accepting the rerouted flight plan that turned a 12 hour travel day into a 36 hour travel day. Acceptance goes a long way in calming you down and preparing you for action.

PLANNING

Here is something I am not an absolute expert in…planning. I have a need to have a plan, but I am often overwhelmed when it comes to details and itineraries and logistics and on and on and on. To me, this can feel suffocating. But one thing that stands out in my first few weeks of the Experiential Education program at MSU Mankato is the theory behind Project Based Learning (PBL). Essentially, PBL demonstrates the benefits of enabling students to observe, interact, experiment and discover solutions through critical thinking. Learning to utilize resources (or thinking creatively with what you have available) is invaluable knowledge that comes from experience and exposure to unique problems.