British Columbia is, arguably, the greatest running destination in the world.

Originally submitted as part of research through Graduate Program at MSU Mankato

Miles of Processing:

Using Running as a Form of Therapy

The first three miles are the toughest. It is a struggle to get into the right rhythm; connecting my breathing with my stride takes patience and understanding. For those first three miles, it is a delicate increase to a harmonious crescendo – a perfect connection between my physical strength and mental acuity. Sometimes, three miles is more than enough. Not because I’m winded or tired or too lazy to continue, but because my brain reaches the capacity for which it can reassess ruminations seemingly at a point I am incapable of controlling. Sometimes that crescendo of understanding comes much later— maybe six or seven miles in—but when I do approach that desired bout of clarity, I can feel a substantial shift in my overall demeanor. I call these mini-epiphany reaching sessions my Processing Miles, or PM’s.

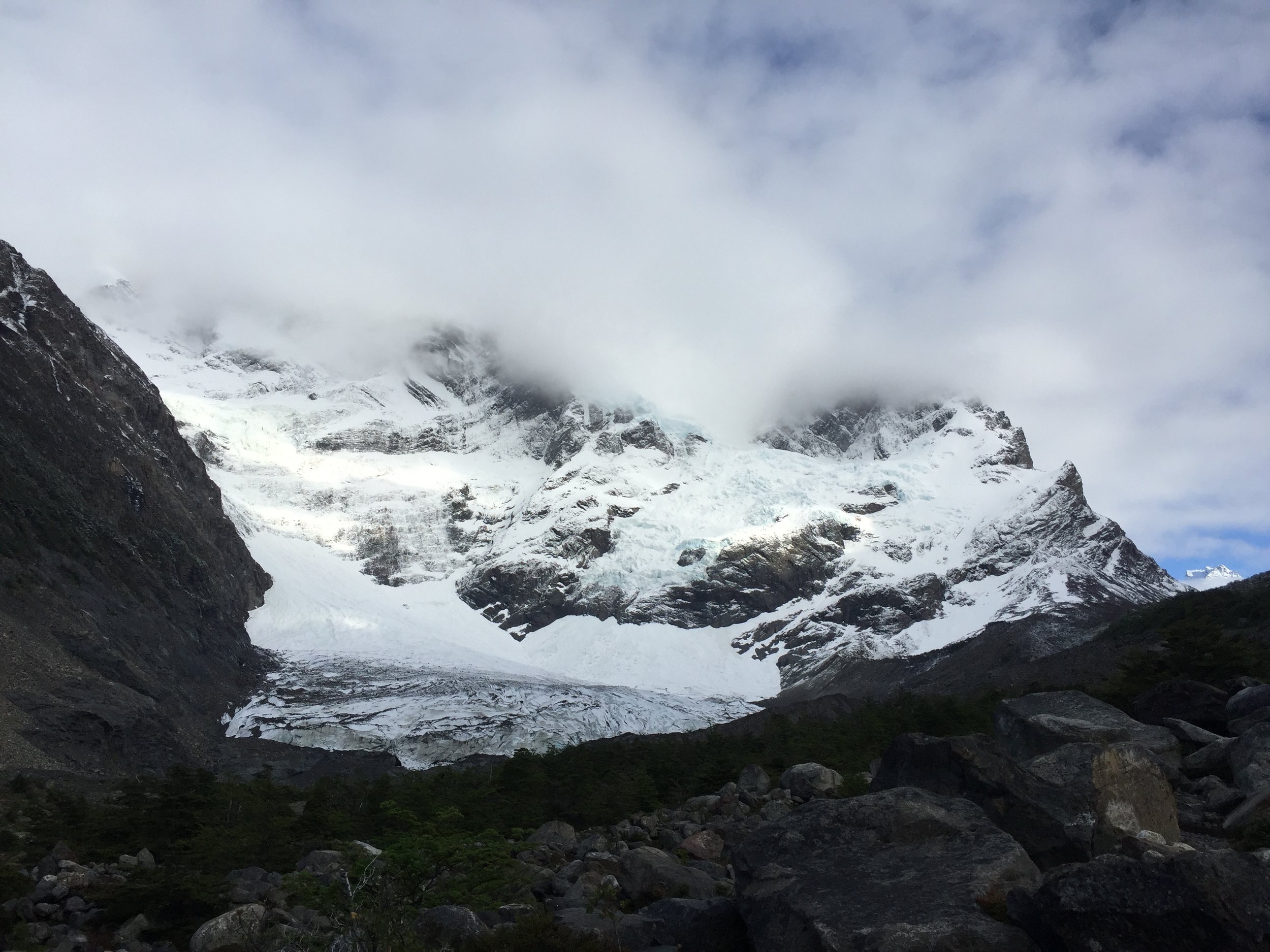

A crucial ingredient to the success of PM’s is the environment. I have never been able to find solace in running inside, whether on a treadmill or an indoor track. The most important part of running, for me, is the connection with nature. Living in a rural area allows me the unbeatable luxury of running endless country roads lined with oversized birch trees, sweeping meadows and endless acres of farmland. The surrounding scenery plays an integral part in my pursuit of running, as it directly affects my ability to relieve stress.

In this instance, running is my own personal form of restoration due to my ability to get away from distractions and focus on one important thing in that moment. To participate in this experience, I must engage in a subconscious practice of moving on from what Kaplan (1995) refers to as “directed attention fatigue” (p. 170). Essentially, the idea is that from an evolutionary standpoint, humans were not designed to withstand attention to one singular detail or project for a long period of time. In retaliation, we have become susceptible to inevitable mental fatigue. As Kaplan suggests, “All too often the modern human must exert effort to do the important while resisting distraction from the interesting” (Kaplan, 1995, p. 170).

This is a wildly modern conundrum, as it is a relatively recent problem (recent as in the past few hundred years) to have to divert our attention to anything other than staying alive. Thus, directed attention fatigue can result in severe consequences within someone’s life or work or both and the understanding of the need for restoration is ever important. Kaplan (1995) suggests four key components to a restorative environment is that it must be far away, fascinating, extensive, and adequate compatibility between the environment and one’s purpose (p. 173). Most notably, the research suggests, “Experience in natural environments can not only help mitigate stress; it can also prevent it through aiding in the recovery of this essential resource” (Kaplan, 1995, p. 180).

While we do our best to avoid stress, it is inevitable. Nature is an incredible resource available to aid in stress relief, as shown by extensive research and, in my case, personal experience. Running has become a form of therapy for me as it gives me the opportunity to reframe problems by means of exercise and extensive time outdoors. I have found, however, that my PM’s have been more valuable in rural areas due to the ability to disconnect from modern luxuries and distractions. This is not uncommon, as research regarding restoration within nature has shown that “…recuperation was faster and more complete when subjects were exposed to the natural settings rather than the various urban environments” (Ulrich et al., 1991, p. 222).

It is interesting that the profound benefits of nature for restorative purposes seem so obvious to me. I rarely question the importance of natural settings as a crucial quality for stress relief because my experience proves it to be beneficial. An important factor to this process, as Kaplan points out, is fascination. The beauty of natural settings is that it offers reprieve from overwhelming stimuli such as car horns, bright city lights, or external conversations. Objects in nature offer a fascination that is more manageable in the background and, unlike harsh light or dramatic noise in urban environments, allows us to focus on other things while engulfed in this environment. Kaplan summarizes this phenomenon as a critical component to a restorative environment:

“Many of the fascinations afforded by the natural setting qualify as “soft” fascinations: clouds, sunsets, snow patterns, the motion of the leaves in the breeze—these readily hold the attention, but in an undramatic fashion” (Kaplan, 1995, p. 174).

Interacting with these natural fascination patterns requires no effort, thus creating an environment for the mind to wander freely and return to a state of positivity. In researching the reactions to natural environments after a form of stress, it was discovered “Findings were consistent with the predictions of the psycho-evolutionary theory that restorative influences of nature involve a shift towards a more positively-toned emotional state” (Ulrich et al., 1991, p. 201). Our society tends to favor the idea of overworking, and with the prevalence of exhausted professionals, spending time in nature is more important than ever to aid in the return to a manageable, positive state of mind.

It stands to reason, then, that this process happening within nature in response to stressful situations can (and should) be applied to various professional settings with high instances of stress and overwhelming directed attention fatigue. Interesting findings have shown, in a healthcare setting for example, that “Instead of providing televisions in these spaces, the research evidence demonstrates that a nature intervention would be significantly more beneficial” (Sullivan & Kaplan, 2015, p. 8). If you think about it as a never-ending cycle, the benefits of nature starting in the healthcare setting could set off a domino effect to the rest of the world in which we live and work. As patients heal faster and with a more positive mindset, healthcare workers are happier, facilities are less stressful environments and healed patients are quicker to return to their industries with a more positive mindset, allowing for the cycle to continue to companions and consumers and so forth. It seems abstract, but the benefits of nature are all encompassing.

There are so many different ways to experience the stress-relieving benefits of nature. For me, running outside has become the most useful form of therapy as it allows me to break away from a hectic lifestyle, focus in on important thoughts, and utilize a distraction-free environment to restore my sanity. I find the best solutions to problems come after those initial few miles—when my body is in sync with the wind, fresh air, and chirping of birds in the distance—and my thoughts have the ability to detach from the day and rearrange.

References

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology,15(3), 169-182. doi:10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

Sullivan, W. C., & Kaplan, R. (2015). Nature! Small steps that can make a big difference. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal,9(2), 6-10. doi:10.1177/1937586715623664

Ulrich, R. S., Simons, R. F., Losito, B. D., Fiorito, E., Miles, M. A., & Zelson, M. (1991). Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology,11(3), 201-230. doi:10.1016/s0272-4944(05)80184-7